When it comes to throwing, most coaches naturally focus on the arm. Arm slot, shoulder rotation, and release point are the details that jump out when you’re watching a pitcher or position player throw. But here’s the truth: what you see in the arm is only the end of a much bigger story.

The quality of movement in the shoulder girdle — and the health of the arm — is directly connected to what’s happening down at the hips.

If the hips aren’t moving well, the shoulder is forced to do more. And in a repetitive, high-stress movement like throwing, that extra demand is a recipe for inefficiency, compensation, and often, injury.

Think of the body as a chain. Every link has to work together to create smooth, powerful movement. In throwing, the hips are one of the most important links.

The hips generate force in all three planes of motion, and transfer energy through the torso and into the arm. When the hips are mobile, strong, and timed correctly, they provide a stable and explosive base. This allows the shoulder girdle and arm to move efficiently without having to overcompensate.

But when hip functions are limited in motion — whether it’s tightness, weakness, or poor sequencing — the chain reaction is immediate. The player will still throw the ball out somehow, so the shoulder girdle starts working harder than it was designed to. Over time, this shows up as poor mechanics, energy leaks, and increased stress on the arm.

The cocking phase is one of the most critical pieces of the throwing motion. Think of it like pulling back the string of a bow before launching an arrow. The body is storing energy, preparing to release it with speed and precision.

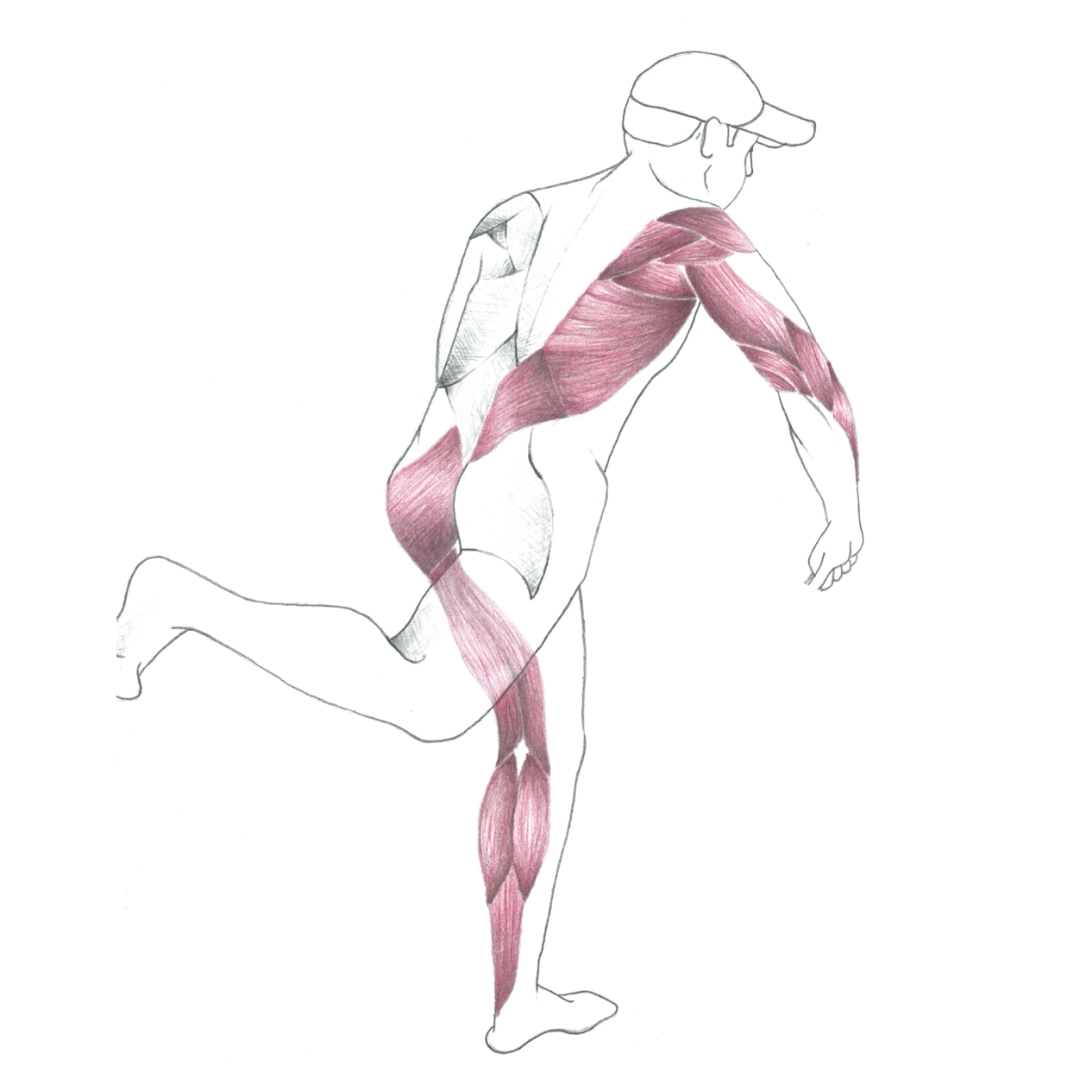

During this phase, the Anterior X Factor comes into play—a chain of muscles, fascia, and joints that runs from the calf, through the inner thigh (adductors), hip flexors, and across the body into the opposite obliques, pectorals, shoulder, and finally the throwing arm. Just like a bowstring or rubber band being stretched, these tissues lengthen, load, and store energy. That stored energy is then unleashed as the pitcher transitions into the acceleration phase. Refer to the Anterior X-Factor image and photo of the archer.

Here’s the challenge: when key areas like the hip flexors or adductors are tight, the bowstring can’t fully load. Instead of efficiently building and transferring energy, the pitcher is forced to compensate. Most often, that compensation shows up as overextending the throwing arm. While it may help the athlete “get the ball out” in the moment, it places unnecessary stress on the shoulder and raises the risk of injury.

For coaches, this means one thing: mobility matters. Optimizing hip and core flexibility ensures the cocking phase works as intended—building elastic energy, fueling velocity, and protecting the arm.

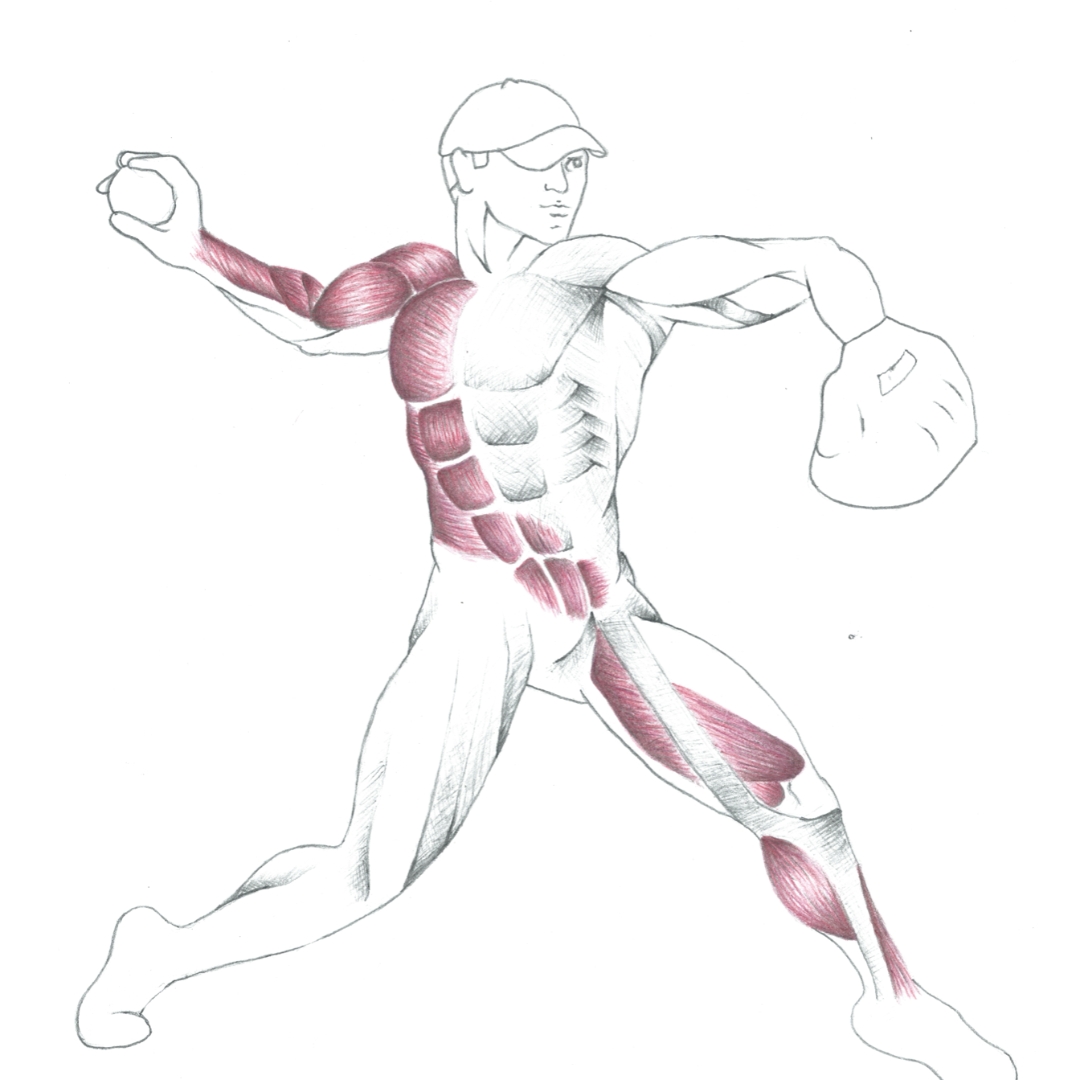

As a pitcher transitions from the acceleration phase into early deceleration, one key movement must happen: the athlete needs to flex, or bend forward, at the hip. This forward hinge allows the body to absorb force and safely transfer energy down the chain.

But when the hamstrings, gluteal complex, or lats on the throwing side are tight—or when motion in these areas is limited—the body finds another way to get the job done. Refer to the Posterior X-Factor image and picture of the pitcher at follow-through). The problem? That “other way” usually means the shoulder ends up making up the difference. Over time, this added stress during deceleration increases the risk of injury, especially to the back of the shoulder or the elbow.

Even more concerning, restricted motion often causes the scapula to protract (move outward) beyond its natural thresholds. When the scapula is forced out of position, it no longer provides a stable base for the shoulder, leaving the arm vulnerable to strain and overuse injuries.

For coaches, this highlights the importance of addressing flexibility and strength not just in the arm, but in the hips, glutes, hamstrings, and lats. Building mobility and stability in these areas gives pitchers the ability to decelerate efficiently, protect their shoulder, and extend their careers. Remember, mobility and flexibility are equally important to overall strength. Make sure to focus on the mobility factor when considering strength and conditioning programs for your athletes.